The Trojan Horse of St. George on Tbilisi’s Freedom Square and What it Tells about Georgia's Democracy

Longer essay now out as a book chapter

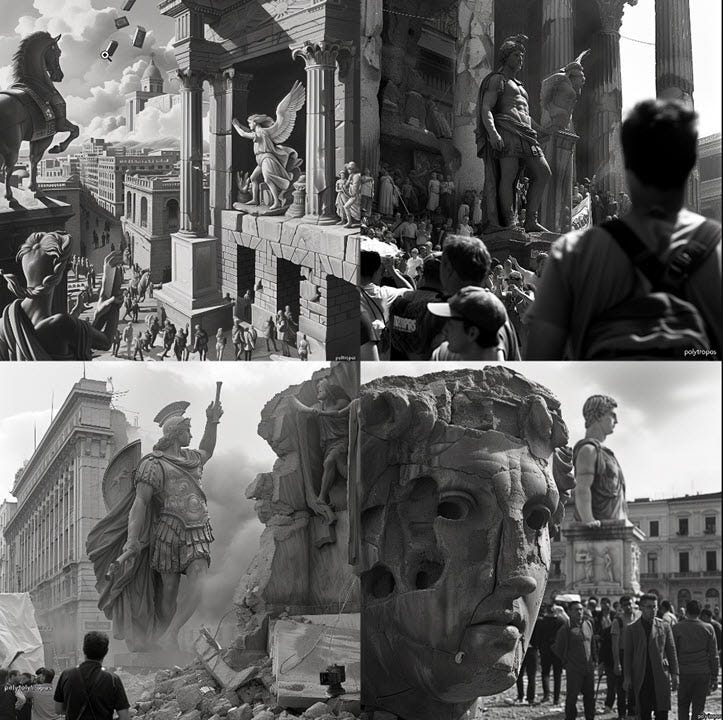

How has Freedom Square gone so spectacularly wrong? The message of Tbilisi's main square seems to be that citizenship does not matter. The square conveys this through a bombastic central column; with Saint George on top, who on closer inspection turns out to be a Trojan horse of sorts; with the buildings that now encircle the square which embody money and power, but in which citizens do not really have a place; and with how people are constrained when navigating a location that should be theirs.

How has this all gone so wrong? How did Georgian citizens come to accept that a crony of Vladimir Putin put up a statue that represents a vision of empire and subjugation, but not of real freedom? What does that tell us about Georgia’s democracy?

I drew out these ideas in a longer essay, written in early 2024, before things began escalating in Georgia. The essay has now been published in a chapter, as part of a book on “The Politics of Post-Conflict Heritage Reconstruction: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives”, edited by Nour A. Munawar and Gertjan Plets, here. The signature quote at the beginning is by Natasha Lomouri:

“Today’s Georgia is a result of mistakes made in the past that we’re continuing to repeat, because we have never had the time to reflect.”

Though the essay was written more than a year ago, a lot remains relevant. There are multiple dimensions to what went wrong with Freedom Square. In a small survey, people seemed to agree that the statue is “terrible art,” “gaudy-gilt-hideous” or “ugly, tacky.” There is a political angle, in that Freedom Square reflects the impatience to make progress after 2003, which Georgia is now paying for, in many dimensions. The statue? It was not made in the city in which it stands, put together in Russia, and then flown in by a large military plane. In a way, the symbol itself undermines Georgia’s freedom.

Many post-Soviet countries (apt name here) need to figure out what to do with the places in which Lenin used to stand. Estonia found a better solution, as far as I could make out.

On a visit to Tallinn in May 2024, however, an Estonian friend grumbled about the monument on their Freedom Square: “The cross needs constant repair, the lights don’t work or the glass panes are falling off.” I said: “Good symbolism. Freedome needs onoging attention.”

His reply: “Yes, but we could use the money to help Ukraine, where actual freedom is defended.”

There are, then, real trade offs to symbolic politics. The monument above, incidentally, does not stand atop where Lenin was, in Tallinn. The Lenin statue has been replaced by a non-descript flowerbed.

Legitimate Authority and the Need for Debate

In Yerevan they are still discussing how to replace Lenin, and in this piece I suggested that Alexander Tamanyan, the city’s main architect, should be moved there, as he recreated a good home for a people who had lost theirs.

You can imagine the enthusiasm you get for trespassing on local debates — but we did have a good debate in Yerevan in February 2024.

One thing that Estonians did, in contrast to the people in too much of a hurry in Tbilisi at the time, was also to have a public debate and a competition. In Tbilisi the decision was top down. This leads to a larger point connected to the Ethics of Political Commemoration, a topic I have been working on for some time. Central squares should have “legitimate authority”, and what happened in the center of Tbilisi illustrates what happens when places do not have that. As I put it in the essay, that is illustrative of various other developments under Saakashvili.

To criticize the decisions of Saakashvili’s government is not to take a cheap shot at someone who is sitting in jail now, sentenced to charges that any reasonable person cannot consider to be fair. Rather, it’s to talk also about things I totally missed at the time. Back then, I had just brought my bike to Tbilisi. On a bike, safely arriving in Freedom Square from Vake, where I lived and worked, felt like winning the Tour de France. I paid attention to not being hit by cars on the ground, not to anything sticking into the air. It only became clear to me much later that something had gone entirely wrong there.

Like the people in charge, I was in a hurry of my own. This is why a structured framework such as the Ethics of Political Commemoration helps us take stock, and the essay outlines how that could work.

What is Special about Georgia’s St. George

Then, of course, there is St. George. In the survey, I got flak for voicing doubts about the figure. “What’s next, you want to take our flag as well?!?” People are sensibly sensitive about others questioning their symbols. But you don’t win freedom by slaying dragons alone. Heroic acts may be part of the struggle but by themselves are not enough. If you think of freedom in epic terms only, you risk not getting or even losing it.

Beyond this metaphorical consideration, looking at St George reveals an even more interesting story than the one most people know. As Kevin Tuite (Université de Montréal) and Sara Kühn (University of Vienna) have pointed out, St. George as a dragon slayer is something that appears to very Georgian. Kühn says that “it is […] very possible that the miracle narrative of Saint George and the dragon originated in the Transcaucasian region, probably in Georgia, from where his cult and his fame spread throughout the Near East, as well as Europe.”

This miracle narrative arose more than 500 years after St. George — a Greek soldier in Cappadocia — was recognized as a martyr. Why? Kühn believes that it’s a fusion with Zoroastrian beliefs. She traces this back meticulously and the version gets at something we forget when we look at a map today: we see Azerbaijan, and forget that it was actually the Persia that was just a day’s ride away from Tbilisi (when Persians were not in control of Tbilisi). The fused figure (the writer Mikhail Javakhishvili already recognized its syncretic character, when the suitability of St. George as a national symbol was discussed more than 100 years ago) in my mind tells an even more exciting story about what makes Georgia special in its own way than the Wahhabi version that we will hear in tourist-guide exhortations.

Moving forward with Freedom Square

The essay considers some ways forward. A new competition? A empty plinth with a rotating statue, as on Trafalgar Square? A soccer fan proposed a statue to the “FC Dinamo Tbilisi team who won the title in 1964 or the Cup Winners' Cup in 1981”, as this presented a truly unifying story. I love how such suggestions can come in.

In the end, perhaps the best idea was to have an ideas competition for those under 25 to see what suggestions they come up with for Freedom Square, to take the politics and the inevitable rivalry of established architects and designers out of it. In a better world, that is what a president’s office could be doing. If it was up to me, I would relocate the current column to Kazbegi, to tell Russians that you can liberate yourself from Tsereteli’s monstrosities.

Right now, of course, the monsters are in ascendance. But other times will come, too. When they come, Georgia will need a “patriotism of reflection” to move both the square and hopefully the country forward, and not to repeat mistakes that were made, as per Lomouri’s quote. Some of the ideas in the essay may help.

For all you academics out there, the essay is accessible here. For non-academics, I can send you a complimentary copy, ping me somehow. I did summarize the most important parts here and the essay had to do a lot of scholarly things, especially in the beginning, but if you bringly saintly forbearance and want to dive all the way in, I am more than happy to share.

[Thanks to all the good people who contributed ideas, Kevin Tuite, Tim Blauvelt, Oliver Reisner who set me on these topics, Natasha Lomouri for the great quote, Khatuna Khabuliani, and especially to Nour A. Munawar and Gertjan Plets for bringing me on board for this book that also has lots of other interesting chapters.]