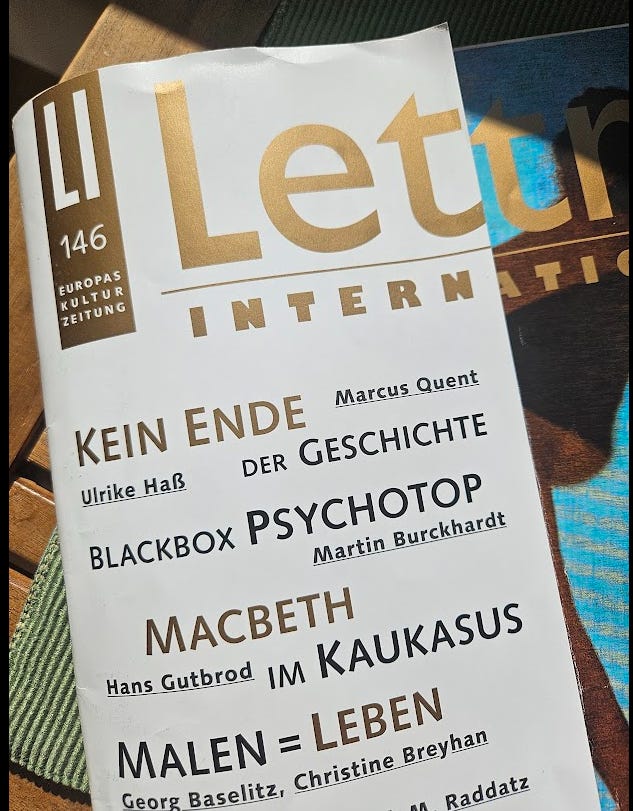

I had several times described Bidzina Ivanishwili as the Macbeth of the Caucasus, and how that framing highlights a range of arguably illuminating parallels. The article has been out in Lettre now since late September, in German, in full length.

If you are in Germany and read German, it would of course be wonderful if you buy the journal, as we need places that publish a full 9900 words when there is something (hopefully) interesting to say. The link to the article is here.

For those that cannot read German but want access, I am in the process of finalizing an English version, hopefully ready tonight. You can ping me directly, and we can take it from there. I may also publish a version behind a paywall, in part to have a sense of who reads this and to still leave options for future publication in English (& to recoup what I paid someone to help smoothen the very rough machine translation).

In part my implicit argument is that certain modes of analysis let us down, and that you do need an essay to get a proper sense of the dimensions of a profound paradigm shift. Policy papers and disciplinary boundaries are of limited use when the very distinctions of policy, politics, law and order are purposefully being blurred and in some cases torn apart.

Here is the outline, and it indeed seemed to be that it is a story that can be told in five acts. (There will be some tweaks to the final English wording still.)

Two added aspects that I did not quite pack into the piece. According to Aristotle, comedies make people look worse than they really are, because it is more entertaining to see a villain stumble over his shoelaces. (The recent French series “Call my Agent” is a perfect example, in heightening the selfishness of most of the key figures.)

Tragedies make people look better than they are, as there is something more moving if people with good or at least reasonable intentions stumble. I wrote this in the tragic register, for multiple reasons. It’s anyway a mode I prefer, but I also think it’s one that makes us think harder than the “this is a bad guy, and that is it.” This also means that this piece likely will fall flat for those who want to read a takedown. (For that mode, read another of my recent pieces, here.) Still, Macbeth is instructive, as I say in the piece — you can have a nuanced take on a figure and still think the results are disastrous.

The essay reflects on some of these questions, and that part is of course for a more general audience, that wonders about these questions in broader contexts, too.

Interested? Ping me in one way or another.

The name seems apt. I look forward to purchasing a copy.

Keenly awaiting. And you should have tossed me the machine edit, I’d’ve done it for the sheer privilege.